Picasso’s Women: Relationships and

Representation

It is said that

behind every great man there is a patient woman. For Pablo Picasso there were

many, but they weren’t always patient. Over his career he entertained six

long-term relationships whose infamous characters and stories are tightly woven

into his work. It is impossible to

study Picasso’s oeuvre without taking a closer look at the evolution of the

representation of women in his paintings and sculptures. Between the years of 1918 and 1935, as

he waltzed from his wife Olga, to his mistress Marie-Therese, to his

distraction Dora Maar, the depiction of women in his paintings under go many

metamorphoses. Giant Greco-roman figures became tortured deconstructed

carcasses and later were reborn as sleeping beauties. Despite the variety of

dispositions, however, throughout the progression the women remain posed

objects under observation, never ascending to the status of an autonomous

subject. For Picasso, his women were his.

There was no easier guarantee of possession than to immortalize them in his

paintings.

1918: The Beginning:

Olga

Seven Ballerina, Pablo Picasso, 1919, paper 62.2 x 50 cm, Musée Picasso,

Paris, France

In 1916, the midst

of the cubist artistic regime in Paris, Picasso was approached by Jean Cocteau

to work on Diaghilev’s latest Russian Ballet Parade. In accepting this project, despite rampant criticism from

his fellow artists, Picasso made his official departure from Cubism. Not only

was this a new leaf in his art but a new chapter in his life, for it is in

Parade that he will meet his future wife Olga Koklova. Between the multiple

runs of Parade and when Olga and Picasso married in

1918 we find many depictions of ballerinas in his work. But they are hardly the

dainty delicate figures often used to represent dancers. Seven Ballerinas (1919), for example, is a drawing based on a

picture of the Russian ballerina’s, in which Olga is positioned front and

center. Their bodies are large, beefy and cumbersome. Their hands are heavy and

masculine yet their poses are traditionally serene and graceful. This

counterintuitive depiction of dancers will set the stage for his complete

inversion in The Dance. But before he

make the jump to those mutilated figures, he continued to add weight and

testosterone to his women as seen in Seated

Woman (1920). Here the body is made even bigger and more hulking. By

alluding to Greco-Roman style, the she seemed to be amassed from stone. A

nearly identical representation occurs in Three

Women at a Fountain (1921) where, although in motion, the women are as

dynamic as statues.

His

bulking and distortion of the feminine form in this post cubist period can be

seen in his work as early as 1918 in The

Bathers. In a setting that demands leisure and comfort, the three women are

contorted and precarious. They are again brutish rather than sexy. Whispers of Guernica originate here in the standing

figure’s violently twisted neck.

The Bathers, Pablo

Picasso, 1918, Oil on canvas, 26.3 x 21.7 cm

Seated Woman, Pablo

Picasso, 1920, Oil on Canvas

Three Women at a Fountain, Pablo Picasso, 1921, Oil on

Canvas, 203.9 x 174 cm

Picasso at

Jean Le Pins, 1924, Photography by Man

Rey.

Where

are is this masculinity coming from? One wonders when comparing them to

Matisse’s voluptuous odalisques of the same period. Perhaps his was Picasso’s

preference for large women. Perhaps it was Olga’s pregnancy in 1920 and the

birth of his son in 1921, the period that marks the deterioration of their

relationship. In which case perhaps the weight of the relationship was bearing

heavily upon him, no longer carefree and fun, it had become heavy and

tormenting. Whatever the reason may be, it is hard not to find Picasso’s

likeness within these figures. His barrel chest and full round facial features

are nearly identical to that of the Seated Woman. Implanting himself in these portraits can be seen as a

assertion of his perceived dominance or vanity. As if to say, “This painting

may be of you, but it’s really about me.”

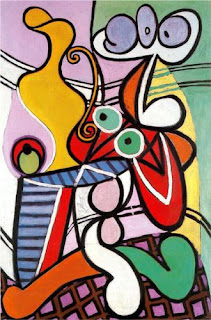

1925: The Breakdown: Three Dancers and The Crucifixion

Three Dancers, Pablo

Picasso, 1925, Oil on Canvas, 215 x 142cm

If the ballerinas of

1918 were a counter intuitive exploration, the Three Dancers are an

antithesis, “a vivid and dramatic rearrangement of the human figure.” (Timothy

Hilton, Picasso) Here the dancers are

aggressive, sharp and dismantled, everything but graceful. All are in simultaneous

agony and celebration. Pain and pleasure, much like that of the relationship

with his own dancer. His palette is hot and harsh as if bursting with every

kind of passion, tragic and triumphant. “The calm and the replete poise of the

figures the women and classical youths are replaced by emaciated, tortured

figures that might be of either sex.” (Timothy Hilton, Picasso) This is an

expressionist piece, that marks the beginning of phase commonly known as “the

attack on the human figure”, and directly channels the experience of his

current relationship with Olga. At this time, their son Paulo now 3, she had

become an increasing source of unhappiness and irritation in his life. Born into the lower echelon of Russian

nobility, Olga assumed when she married Pablo, at that time on the lower echelon

of Artistic nobility, they would lead a “soft, pampered, upper-crust life.”

(Francoise Gilot, My life with Pablo) But Pablo, dedicated to his art and his

life style, maintained his vie boheme and remained independent. On a visit to

his mother in Barcelona before their marriage she warned Olga against the

marriage, “[Don’t] do it under any conditions. I don’t believe any woman could

be happy with my son. He’s available for himself but for no one else.” (

Francoise Gilot, My Life with Picasso) Stubborn and determined Olga continued

to attempt to pull Pablo to her will, a crusade we can imagine only pulled her

closer into Pablo’s force field of control.

(Left) Seated Woman,

Pablo Picasso, 1927, Oil on Canvas

(Right) Large Nude in

a Red Arm Chair, Pablo Picasso, 1929, Oil on Canvas,

By 1927 Picasso is

no longer giving her the luxury of a backbone, she is rather a wailing pile of

flesh and genitalia as in Large Nude in a

Red Arm Chair (1927). “We very

often find that the figure, in these paintings, is looped in and trapped by the

very line which defines it.” (Timothy Hilton, Picasso, 164) This practice is true of Seated Woman (Olga) (1927) as well as Three Dancers (1925). Perhaps this representation should come as no

surprise because, after all, it was Picasso

who defined Olga. Or rather he held the line that could either bind her to him

or let go of and unravel her. And so he did, in 1935 when he left her for his

mistress Marie Therese and his new born child Maya.

But

this split did not come before perhaps the most agonized of paints during their

relationship. In 1930 he chooses a traditional subject infinitely visited in

the history of art and western civilization; a crucifixion. Despite the

unavoidable religious connotation of the subject, Picasso himself was not religious,

in face he was an atheist. If not Christ, who then is being crucified? The same

wailing open mouth we see in The Large

Nude in a Red Arm Chair (1927) appears here as well. But here, it more

strongly resembles the form of a praying mantis, an insect known for the female

eating its mate alive after sexual intercourse. Is the figure on the cross a wailing female? Or a crucified

Picasso being eaten alive by his mate?

La Crucifixion, Pablo

Picasso, 1930, Oil on Canvas, 50 x 65.5 cm

1931: The Dream:

Marie Therese

Woman with Yellow

Hair, Pablo Picasso, 1931, Oil on Canvas

Beginning in 1931

we begin to see a more supple gentle figure dominating his work, a sleeping

beauty at peace. Picasso met Marie Therese Walter in 1930 on the street in

Paris when she was just 17 years old. “Je suis Picasso,” he told her “vous et

moi, allons faire de grandes choses ensemble” (Picasso, 1930) and thus began

their affair. With an arresting face, Grecian profile, and full athletic build

she was Picasso’s idea of perfection. Not only physically perfect, but psychologically as well. “She was

the luminous dream of youth, always in the background but always within reach

that nourished his work.” (Francoise Gilot, My

Life with Picasso) In Marie Therese Picasso could escape from the public

life, the intellectual life and

most of all his life (with Olga) and all was calm because she was an escape. The first portrait of her

is hardly a portrait at all, but rather a still life with a secret subtext. Great Still Life of a Pedestal Table (1931)

is blooming with soft joyous colors, as stark contrast from the firey reds of The Crucifixion. Within the rounded forms of the table,

vase, and fruit we see Marie Therese’s form emerge. The two pieces of fruit on

the table can be either her eyes or breasts, as the tables legs become her

limbs. The red crooked form on the right resembles the bent elbow she often

rests her drowsy head on in later portraits like Woman with Yellow Hair. She is always represented in a beautiful light,

but she is also always being watched over. She is on his terms. He watches her

as she dreams because she is his dream, not the other way around. We see this

in The Mirror (1932) she is being

watched over from two angles, the reflection of her broad shoulders in the

mirror behind her, and from Picassos gaze as he paints her. She is his from all

angles. “She was a dream and the reality was someone else. He continued to love

her because he hadn’t taken possession of her.” (Francoise Gilot, My Life with Picasso) Her portraits are

composed whimsically as if she is always at risk of a night breeze blowing her

away. As in anything too good to be true, the perfection is fleeting and

delicate, prone to evaporate into thin air.

(Left) Great Still Life on a Pedestal Table, Pablo Picasso, 1931, Oil on

Canvas.

(Right) The Mirror, Pablo Picasso, 1932, Oil on Canvas

1937: The War: Marie

Therese and Dora Maar.

Though unable to official divorce her

without forfeiting half of his work, Picasso left Olga in 1935 and their

separation allowed for Marie Therese to finally assumed publically the premier place in his heart. But it

wasn’t long after they were freed from the secrecy of the affair that the reality

of their relationship began to set in. Now that she was fully his, in his

possession, and she was no longer a dream or imaginary. The mundane inherent

difficulties of relationships arrived- fatherhood, responsibilities, jealousy,

misunderstanding- difficulties he had formerly been able to avoid in his double

life. At this point he needed another distraction, and so entered Dora Maar in

the same year. While Marie Therese

was gentle, passive and obedient, Dora was intelligent, bold, and head strong.

A photographer herself, Picasso took a great interest in her as “someone he

could carry on a conversation with.” (Picasso, My Life With Picasso)

Picasso painted

many portraits of his two lovers, each with their own distinct style. Often the

two women are depicted together as in Seated Woman

in Front of a Window (1937) to represent the simultaneous presence

they had on his life during that time. In these portraits Marie Therese

maintains her round, lyrical form but her unhappiness and jealousy of this

period tint the figure more sober shades of blue and green. Dora Maar is

usually represented by wild colors, and angular jagged shapes.

(Left Crying Woman (Dora Maar), Pablo Picasso, 1937, Oil on Canvas

(Right) Sleeping by the Shutters (Marie Therese), Pablo Picasso, 1936, Oil

on Canvas

As one can

imagine, the two women did not take lightly to sharing a lover and a great

conflict arose between them. Far from disrupting Picasso, this constant

friction stimulated him creatively. “This phase of his painting, which seems to

alternate between happiness and unhappiness, needed them both for

completeness.” (Francoise Gilot, My Life

with Picasso) He enjoyed the dichotomy of the two women’s personalities and

enjoyed even more the intoxicating power he had over them.

“I remember one

day while I was painting Guernica… Dora Maar was with me. Marie Therese dropped

in and she found Dora there, she grew angry and said to her, “I have a child by

this man. It’s my place to be here with him. You can leave right now.” Dora

said, “ I have as much reason as you have to be here. I haven’t borne him a

child but I don’t see what difference it makes.” I kept on painting and they

kept on arguing. Finally Marie-Therese turned to me and said, “ Make up your

mind. Which one of us goes?” It was a hard decision to make I liked them both,

for different reasons: Marie Therese because she was sweet and gentle and did

whatever I wanted her to do, and Dora because she was intelligent. I decided I

had no interest in making a decision. I was satisfied with things as they were.

I told him they’d have to fight it out themselves. So they began to wrestle.

It’s one of my choicest memories.”

-Pablo

Picasso

Guernica, Pablo Picasso, 1937,

Oil on Canvas

Guernica was historically painted

in response to the bombing of Guernica, Basque country by the Germans and

Italians during the Spanish Civil War. But it also can be seen as an

expressionist representation of the war going on 7 Rue des Grands Augustins. The

large female head flowing out the window is clearly Marie Therese and Dora

Maar, as she often was, is the “wailing woman.” And there in the corner we is

Picasso, the shorting bull. In Guernica, we

see his progression of women parading and trampling over the dismembered bodies

on the ground. The experiments and representations he chose 17 years prior

continue to appear. The distorted

immense female form of the Olga days is present in the bottom right. The

violent neck twist of Three Bathers

(1920) gives the wailing women her despair. The looping lines that make up the horse’s figure in the

middle, are the very same that formerly defines Olga. Marie Therese face is

still beautiful, albeit quite unhappy.

Had it not been

for the impatient women in Picasso’s life many of his best and most revolution

works would not exist. They entertained him, bore him children, went mad for

him, fought over him, lived for him. Far from doting, affectionate and

romantic, it is clear Picasso his believed his role in the relationship to be

that of the possessor. The women forfeited their autonomy upon falling in love,

but they sold their souls when he painted them. In his paintings he owned them

by immortalizing their likenesses and temperaments through his gaze. Known to

be a collector of objects and things that inspired him, Picasso collected

women. Until his death they all remained an active presence in his life because

he kept them there, tugging on the lines he once defined them with and never

setting them free.